Surrounded by great prairies as well as great lakes, McHenry may not be the first place you’d expect to find complicated ocean study. But that’s exactly what high school environmental science students are doing, thanks to Adopt-A-Float program that offers schools access to study the health of global oceans for free.

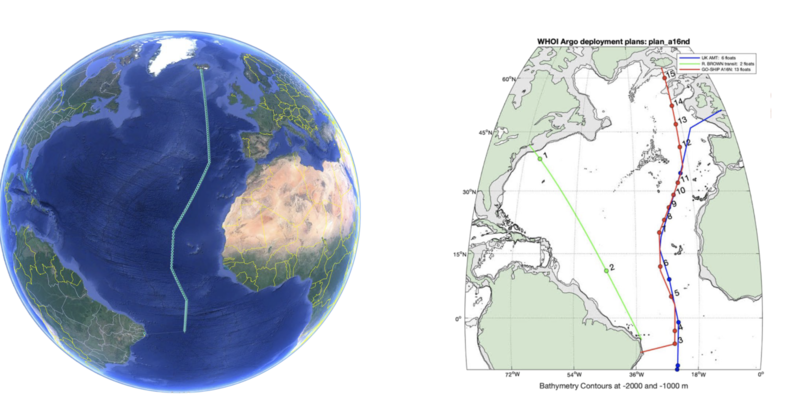

Earlier this month, McHenry Community High School’s very own float was dropped into the Atlantic Ocean somewhere between Greenland and Africa. Every 10 days it will surface and share data from its deep dives with the GO-BGC program and McHenry students.

Tim Beagle, science division chair for McHenry Community High School, said he saw the float as a great opportunity to bring the ocean into the classroom.

“Because we don’t live near the ocean, we don’t have that much experience with it,” Beagle said.

Beagle said he’s hoping to not only have students study data from the float, but also incorporate it into the curriculum through possible web meetings with scientists and other activities.

On a yearly basis, the environmental science students will study data not only from the MCHS float but data from other schools to collaboratively study changes in ocean chemistry latitudinally through the ocean. That information will help students understand patterns and changes in the world's oceans, Beagle said. Students also will have the opportunity to connect as “citizen scientists” with other students across the country, as well as with the scientists from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Dr. George I. Matsumoto, senior education and research specialist for the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute – one of several organizations involved in the Adopt-A-Float program – said he’s excited to offer students a chance to share in the project. This project, named GO-BGC (Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Array) follows a similar program in the southern ocean surrounding Antarctica.

This project came about through a $52 million grant from the National Science Foundation to Matsurmoto’s agency and several others, including NOAA. Ultimately, it involves deploying 500 floats that cost $100,000 a piece. Schools can partner for free.

“It’s been a fun project, and students are enjoying it,” Matsumoto said.

Scientists have been studying the temperature of the oceans for many years but the Adopt-A-Float program builds on that by also measuring oxygen, pH, chlorophyll and nitrate. After providing baseline data, scientists can track changes over time.

Matsumoto said he hopes bringing the program to schools will show students that you don’t have to be a scientist to study the ocean, and that there are many different vocations that can have an impact in improving the planet, such as engineers and machinists.

Also, Matsumoto is hoping that students will see that failure is part of the learning process. Pressure issues with putting the floats in the water has caused some problems for scientists, such as at least one float imploding years ago.

“Failure is part of everyday life,” he said. “It’s OK to make mistakes as long as you learn from them.”